The American military is moving away from its traditional focus on governance and counterinsurgency in Africa, instead pushing partner nations to take greater responsibility for their own security.

The change was evident at African Lion, the Pentagon’s largest joint exercise on the continent, where leaders stressed independence over long-term stabilisation efforts.

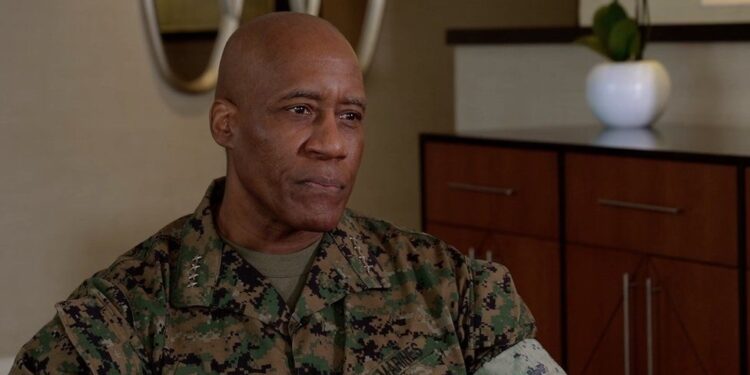

“We need our partners to reach a level where they can operate on their own,” said Gen. Michael Langley, the top U.S. commander in Africa, in an interview. “There has to be burden-sharing.”

For a month, troops from over 40 countries practised aerial, land, and maritime drills—flying drones, simulating combat, and firing precision rockets in the desert.

While the exercises resembled past editions of African Lion, now in its 25th year, the messaging has shifted. Gone is much of the rhetoric about governance and development that once distinguished U.S. strategy from rivals like Russia and China.

Instead, the focus is on helping allies strengthen their defences, a priority under the current administration. “Our goals are clear: protect the homeland and encourage partners to address global instability,” Langley said, pointing to U.S. support for Sudan as an example.

The pivot comes as Washington reshapes its military into a “leaner, more lethal” force, possibly reducing its footprint in Africa even as China and Russia expand their influence. Beijing runs extensive training programs for African armies, while Moscow’s mercenaries solidify their role as security providers across North, West, and Central Africa.

Just a year ago, Langley championed a “whole of government” approach that combined defence, diplomacy, and development to fight insurgencies. He argued then that military force alone couldn’t stabilise weak states or prevent violence from spreading.

“AFRICOM isn’t just a military organisation,” he said in 2023, calling good governance the key to tackling threats like extremism and climate-driven crises.

That philosophy has since taken a backseat, though Langley noted successes in places like Ivory Coast, where security and development efforts reduced jihadist attacks near its northern border. Still, progress is uneven.

“I’ve seen steps forward and steps back,” said Langley, who will leave his post later this year.

The new approach comes despite glaring gaps in African militaries’ capabilities and the growing reach of insurgent groups. A senior U.S. defence official, speaking anonymously, called Africa the “epicentre” of both al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, with the latter shifting command operations to the continent.

Though Africa remains a lower Pentagon priority, the U.S. still stations about 6,500 troops there and spends hundreds of millions on security aid. In some regions, Washington competes directly with Moscow and Beijing; in others, it conducts strikes against militants.

Yet as violence surges, the idea that African armies can soon contain threats alone seems unrealistic. Beverly Ochieng, a Control Risks analyst, noted that even before Western influence faded in the Sahel, local forces lacked the tools to fight extremists effectively.

Now, with Western powers scaling back – either by choice or after being expelled by hostile regimes – the challenges have only grown.

“Many African militaries lack strong air power and struggle to track militants in areas with poor roads and infrastructure,” said Ochieng, who specialises in the Sahel.

In Somalia, despite years of U.S. airstrikes against al-Shabab and IS, the national army remains far from self-sufficient. “They’re improving but still need battlefield support,” Langley admitted.

Across West Africa, the situation is even grimmer. The Sahel alone accounted for over half of global terrorism deaths in 2024, per the Institute for Economics and Peace. Somalia made up another 6%, underscoring the persistent threat.