Africa is reeling under the mounting impacts of climate change, with scorching heatwaves, devastating floods, and prolonged droughts displacing hundreds of thousands, disrupting education, and pushing food systems to the brink of collapse, according to a sobering new report from the UN’s World Meteorological Organisation (WMO).

The continent’s temperatures in 2024 soared to 0.86°C above the 1991-2020 average, with North Africa experiencing the most dramatic warming at 1.28°C above baseline levels – the fastest rate observed anywhere in the world. Surrounding oceans have also reached alarming temperatures, particularly in the tropical Atlantic and Mediterranean, where marine heatwaves of extreme intensity have become increasingly common.

WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo painted a grim picture of the cascading effects, stating that climate impacts are now “hitting every single aspect of socio-economic development” across Africa. The report documents how these changes are compounding existing challenges of hunger, instability, and displacement while placing unbearable strain on vulnerable communities.

The climate chaos has manifested in dramatically different ways across regions. In West Africa, catastrophic flooding claimed 230 lives in Nigeria’s Borno State alone last September, displacing 600,000 residents and contaminating critical water supplies in displacement camps. Meanwhile, Southern African nations including Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe endured their worst drought in at least two decades, with cereal harvests plummeting by 43-50 percent below five-year averages.

The educational consequences have been particularly severe, with South Sudan forced to shutter schools when temperatures hit a blistering 45°C last March. According to UNICEF data, extreme weather events disrupted schooling for an estimated 242 million African children in 2024, with sub-Saharan Africa bearing the brunt of these closures.

Nowhere is the climate injustice more apparent than in South Sudan, a nation responsible for just 0.004 percent of global emissions yet trapped in a vicious cycle of climate disasters. Last October’s floods affected 300,000 people in the war-scarred nation and wiped out between 30-34 million livestock – roughly two animals per inhabitant. The stagnant floodwaters spawned disease outbreaks, while severed transport routes forced humanitarian agencies to resort to costly airlifts of food aid as international funding dwindles.

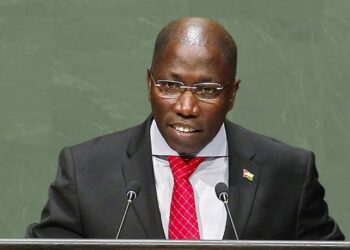

“These climate shocks erase years of hard-won progress in a matter of days,” said Meshack Malo, South Sudan Country Representative for the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. “When families who had achieved self-sufficiency are suddenly forced back into dependency on food aid, it doesn’t just threaten their survival – it erodes their dignity.”

While some adaptation efforts show promise, such as water harvesting projects in Kapoeta that have reduced dry months from six to two, experts warn these piecemeal solutions are inadequate against the scale of the crisis. WMO’s Dr. Ernest Afiesimama emphasized that large-scale investments in early warning systems and climate-resilient infrastructure are urgently needed, rather than relying on stopgap measures like desalination which remains economically unviable for most African nations.

As the El Niño weather pattern continues to exacerbate extreme conditions, the report underscores how climate change has become what Malo describes as “the ultimate risk multiplier” – intensifying conflicts over dwindling resources and threatening to reverse decades of fragile development progress across the world’s most climate-vulnerable continent.

With marine ecosystems warming at alarming rates and terrestrial temperatures continuing their upward trajectory, the findings sound an urgent alarm for international action to support African nations in building resilience against the escalating climate emergency.