By Ere-ebi Agedah Imisi

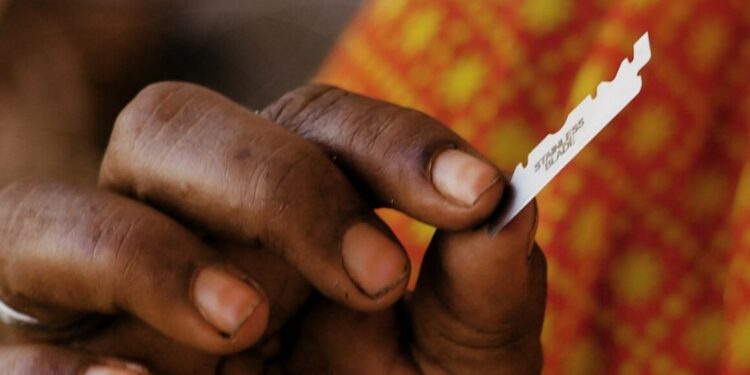

Health and development experts have renewed calls for decisive action against female genital mutilation (FGM), warning that the practice poses severe health risks and remains a major public health and human rights concern in Nigeria.

The experts spoke on Friday to mark the International Day of Zero Tolerance for FGM, observed under the 2026 theme, “Towards 2030: No end to FGM without sustained commitment and investment.”

A gynaecologist, Dr Olufiade Oyerogba, said FGM has no medical or health benefits, stressing that it is associated with serious short- and long-term complications. From a gynaecological and public health standpoint, she explained that victims often suffer severe pain and bleeding, shock, infections and sepsis, injuries to surrounding tissues, and, in extreme cases, death.

According to her, long-term consequences include chronic pelvic pain, recurrent urinary tract and genital infections, menstrual difficulties, increased risk of stillbirth, and neonatal death. She cautioned parents against the practice, noting that claims linking FGM to morality, fertility, or improved marriage prospects are unfounded.

Dr Oyerogba urged governments and policymakers to strengthen enforcement of anti-FGM laws while investing in education, women’s empowerment, and community engagement. She described FGM as a preventable form of violence, emphasising that harmful cultural practices must be abandoned.

“FGM is not a cultural inevitability. Culture is dynamic, and practices that harm girls and women should be stopped. Ending FGM requires collective responsibility, not silence,” she said.

She noted that about 20 per cent of Nigerian women aged 15 to 49 are estimated to have undergone FGM, placing Nigeria among countries with the highest absolute number of affected women globally due to its population size. Prevalence, she said, varies across regions and ethnic groups, with higher rates reported in parts of the South-East, South-West, and South-South. However, she added that declining rates among younger age groups point to the positive impact of education, advocacy, and policy interventions.

While acknowledging Nigeria’s efforts, including the Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act of 2015, state-level laws, and community-based awareness programmes, Dr Oyerogba said enforcement gaps, cultural resistance, and the medicalisation of FGM remain significant challenges. She called for the integration of FGM prevention into routine maternal, adolescent, and reproductive health services.

A UNICEF field officer on FGM, Dare Adaramoye, said the persistence of FGM in some communities is driven by deeply rooted cultural norms, gender inequality, and misconceptions about its purpose. He explained that UNICEF works with governments and civil society to engage boys, girls, women, and men in challenging beliefs that sustain the practice.

According to him, UNICEF also supports the enforcement of laws criminalising FGM and provides assistance to survivors through livelihood programmes, access to free healthcare, and surgical interventions, among other forms of support.