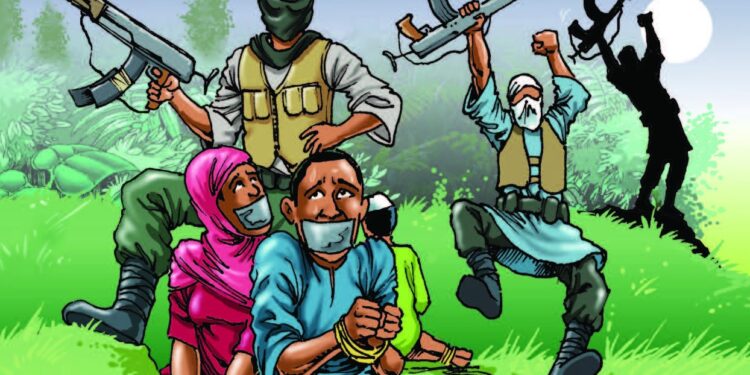

Between July 2024 and June 2025, Nigeria’s kidnap-for-ransom scourge hardened into a full-blown industry, draining household wealth and eroding investor confidence.

This is according to a new report by SBM Intelligence, showing that at least 4,722 people were abducted in 997 incidents nationwide, with kidnappers demanding nearly ₦48 billion and receiving verified payments of ₦2.57 billion ($1.66 million).

Threatening Nigeria’s Economy

While ransom sums are rising, naira depreciation has slashed their value in dollar terms. For instance, ₦653.7 million collected in 2022 amounted to $1.13 million, but the ₦2.57 billion secured in the past year translates to just $1.66 million. In response, gangs now demand higher naira payments to cushion against currency erosion, mirroring how businesses adjust to inflation.

The Northwest region remains the epicenter of abductions, accounting for 42.6% of incidents and 62.2% of victims. Zamfara alone recorded over 1,200 victims, followed by Kaduna and Katsina. The region’s vast ungoverned territories and entrenched bandit networks have turned kidnappings into a large-scale enterprise. By contrast, the Southwest recorded just 5.3% of cases and 3% of victims, offering a relative safe zone for businesses, though the national perception of risk continues to dampen investment.

Mass abductions and incidents with more than five victims, made up almost a quarter of all cases, with villagers increasingly forced into labor on farms and mining sites controlled by armed groups.

Analysts warn that kidnapping is no longer just about ransom but also about broader economic exploitation.

Regional ransom dynamics also reflect this sophistication. In Delta State, one gang demanded an eye-watering ₦30 billion, underscoring the high stakes in the oil-rich South-South. In the Northeast, ransom payments were highest, with nearly ₦766 million, almost 30% of the national total, reportedly paid to free Justice Haruna Mshelia, abducted by a Boko Haram-linked faction. Islamist groups are increasingly using ransom as a revenue stream to fund logistics and arms.

Religious leaders have not been spared. At least 17 Catholic priests were kidnapped during the period, with ₦460 million demanded and ₦70 million eventually paid. While fast-tracked settlements reduced fatalities, intermediaries have come under growing risk, with some killed or abducted during exchanges.

The economic fallout is significant. Rural farmers abandon fields or pay “taxes” to bandits, worsening food inflation. Businesses are weighed down by relocation costs, insurance, and security spending, while smaller firms often shut down under the strain. Larger corporations scale back expansion, particularly in vulnerable sectors such as mining, logistics, and agribusiness.

Concerns For Foreign Investors

For foreign investors, the data reinforces long-standing fears: Nigeria’s insecurity is not only persistent but increasingly commercialized. SBM warns that the so-called “ransom economy” is redirecting liquidity from households and businesses into criminal networks, fueling terrorism and damaging Nigeria’s risk profile.

Public faith in security forces continues to collapse, with 68% of Nigerians rating their performance poorly. The rise of vigilante groups offers temporary relief but adds another layer of unpredictability, as some resort to extortion themselves.

Analysts say Nigeria risks institutionalizing kidnapping unless urgent reforms are undertaken. Without disrupting ransom flows, improving rural governance, and stabilizing the economy, the line between organized crime and insurgency will continue to blur. For businesses, this means higher operating costs and restricted reach; for households, an ever-present threat to survival.